Semiconductor fabrication lays the foundation for microchip production and therefore helps to make our world go round in many ways, as chips do not only power computers, smartphones and other consumer electronics, but are also a mainstay of the automotive industry, control medical devices and keep network infrastructures running.

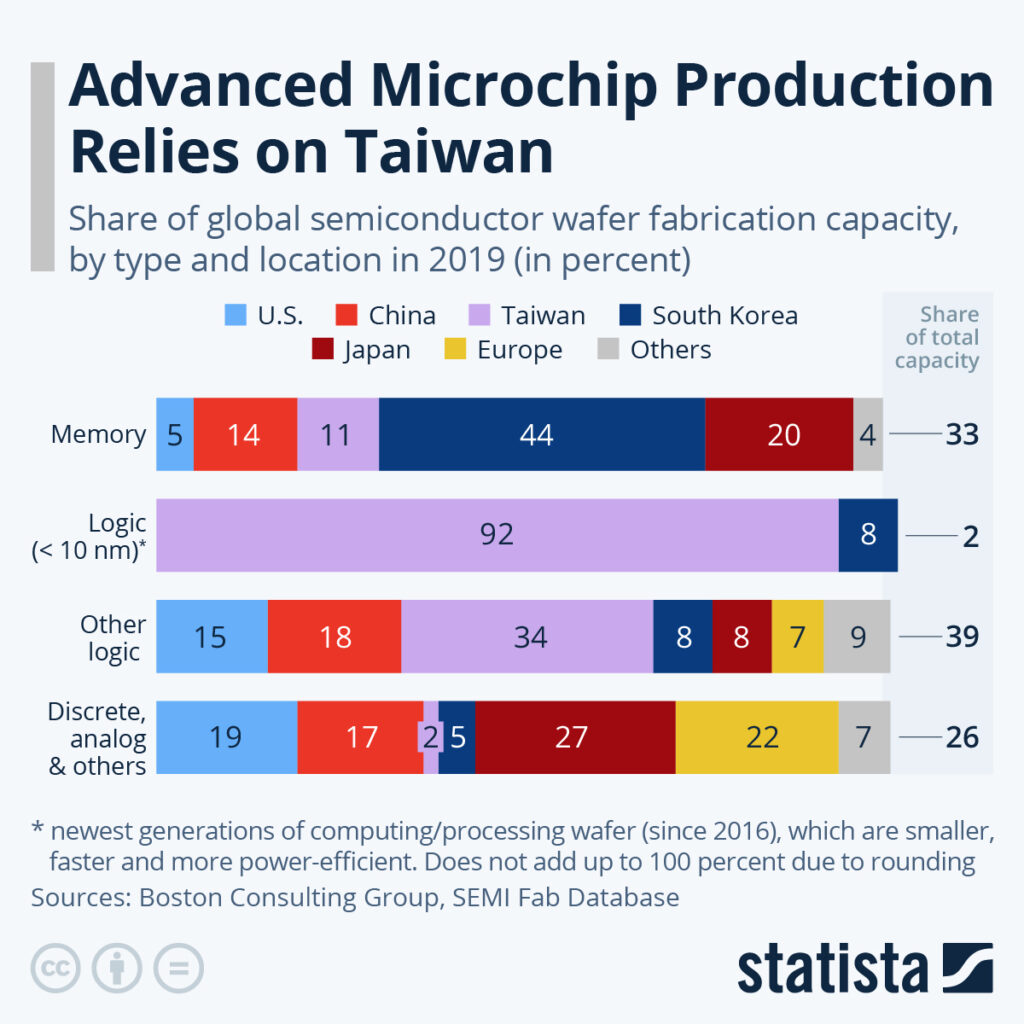

Data published by Boston Consulting Group shows just how concentrated in one place the production of semiconductor slices – so-called wafers – for the most advanced types of computing and processing chips is. Taiwan is home to 92 percent of the production of logic semiconductors whose components are smaller than 10 nanometers (fitting more processing capacity onto a smaller area while also being faster and more energy-efficient).

Semiconductor processes smaller than 10 nanometers were pioneered in Taiwan and South Korea. Other production centers failed to follow suit in producing this type of advanced wafer for logic chips, as the graphic with data from 2019 shows. While the type made up only 2 percent of global semiconductor production capacity that year, its share is expected to grow as part of the ongoing innovation in the sector and it is already instrumental in cutting-edge technology, for example in smartphones.

Over the course of the pandemic, not much changed concerning production locations, but governments are now beginning to act. After chip shortages following Covid-19 supply chain upheavals and geopolitical tensions between China and Taiwan also running high in 2022, the government of the United States as well as the European Union, both dependent on state-of-the-art microchips, have started initiatives to challenge the status quo. Looking at the giant global disparities in semiconductor production, however, it might be a long way until real change can be achieved. For example, U.S. chipmaker Intel is just now rolling out its first below 10 nanometer product, while the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Companyhad done so in 2016.

Both Europe and the U.S. used to hold larger parts of global semiconductor production capacity and were also once quicker to adapt to innovations in the sector. In 1995, Europe and the U.S. had a combined global production capacity share of 36 percent, compared to less than 20 percent today. Including only larger wafer slices of eight inch diameters or above – an innovation of the early 1990s – their combined production capacity stood at more than 80% as early as 1990.

Courtesy: statista.com